Kissing and killing

The Sunday Times, 5 February 1995

By Penny Perrick

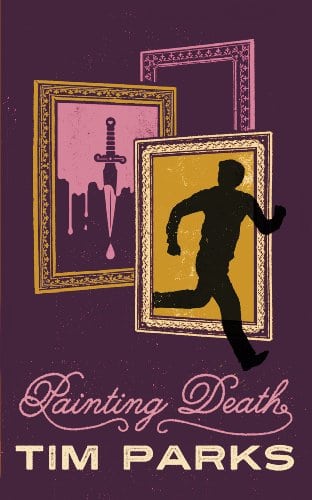

Tim Parks’s murderous anti-hero, Morris Duckworth, first appeared in an earlier book, Cara Massimina, a sourly macabre entertainment whose style has been compared to Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley sequence. In Cara Massimina, Morris dispatched a lecherous Italian and his irritating English lover, as well as Massimina herself, the doting, dim-witted girl whom Morris had kidnapped. Like Tom Ripley, Morris kills for convenience and again, like Highsmith’s creation, he is an unabashed bon vivant.

The similarities end there. Ripley is a smooth operator, poised and deft in his dealings with his victims. Morris is a hapless fumbler, a master of bad timing. Ripley is ruthlessly amoral, a hard man. Morris is whingeingly self-justifying, at odds with himself, unnerved by his Lawrentian background (coarse father leerring at him for his poncy fondness for books, martyred mother investing all her love in him before dying prematurely). Morris has none of Ripley’s menacing presence; he is a study of the slaughterer as flibbertigibbet, rather like the protagonist of Michael Dibdin’s Dirty Tricks.

In Mimi’s Ghost, Morris is at it again, kissing and killing, plotting and panicking. No longer an impoverished teacher of English in Verona, he is married to Paola, older sister of the murdered Massimina (Mimmi for short) but as unlike her as tiramisu is to tapioca pudding.

Paola sees Morris for what he is (well almost, she doesn’t suspect him of Mimi’s murder): a bad lot, in spite of his recently acquired, no-expense-spared polish. She is turned on by the devil within, more spectacularly than Morris, who is as prim as he is perverted, would wish. Disconcerted by his wife’s sluttish antics, and being something of a twisted fabulist Morris is soon conjuring up visions of the dead Mimi, last seen being shoved into a refuse sack by one M Duckworth. The ghostly Mimi suggests good works as a shining path to redemption. Morris, not one to shirk from the absorbing task of reinventing himself, becomes kinkily religious, to Paola’s derisive amusement, and the unlikely champion of the oppressed, in this case a bunch of African immigrants, illegally sheltering in Verona’s cemetery. Morris, giddily sociable and no end of a busybody, finds the men jobs in his in- laws’ wine-bottling factory and houses them with a dubious expat English academic. Before you can say Tintoretto, a den of iniquity has begun to flourish.

Parks writes with a brutal, snapping wit. reinventing the crime novel as a capricious, campy romp. Morris, a despicable scoundrel who fancies himself as a latter-day Rupert Brooke, is shockingly convincing as an accidental assassin. Forced to kill his brother-in-law, who has begun to sniff around the circumstances of Mimi’s kidnap, Morris thinks, ruefully, “Oh shit! Every time you did this business you had to remember every- thing all over again. Because he wasn’t a professional murderer, as in love he could never be a Don Juan Moments later, examining copies of his own ransom demands, be regrets not having asked for more money.

Professional murderer, or just an amateur with attitude, Morris definitely prefers people more dead than alive, one of the reasons why potential murder weapons – a plant pot a paperweight, a chair – slide into his hands so opportunely. Savouring his mother-in-law’s demise (strangely enough, from natural causes), “Morris noted how extraordinarily well the coffin blended in with the rest of the room…Perhaps no provincial was truly complete until it had its coffin.” And further disturbing musings: “He was an artist in the end, that was his problem: the carnival, the I wake, the nuptial bed. They were all the same to him.”

(…) is strewn with the corpses of people who might have come between Morris and his refined mid-afternoon refreshments at the Bar Baglioni. By the end of the book, Morris’s handsome face has been chewed to a pulp by a guard dog, but he’s as slippery as ever, dodging prosecution through a blend of brio and bluff in one of the funniest trials in fiction, which takes place under an anatomically incorrect frescoed ceiling.

Parks leaves us in little doubt that Morris will carry on killing. As Morris himself bluntly points out: “Anyway, the thing to remember was that however someone was really murdered there was always another completely feasible way in which they might have been, because in the end so many of us have such excellent reasons for wanting to do away with each other.” A piece of conclusive reasoning that leaves the reader collapsing into squeamish giggles.