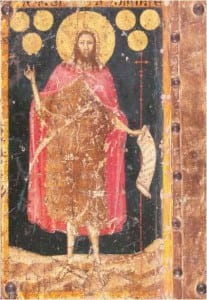

Fra Angelico “could have become rich, but made no effort to do so.” So Vasari tells us. Instead he painted for the wealthy. Privately commisioned, this painting was intended to enhance the quality of a rich man’s prayers. The viewer is not reminded that Christ was born in poverty. Francesco Datini advised agents procuring devotional paintings to wait until artists were in need of money, then talk down their prices.

Blue paint: 2 florins (approx). Gold background: 38 florins (approx). Artist’s work: 35 florins (approx)

Fra Angelico «potette essere ricco, e non se ne curò». Così dice Vasari. Si limitò a dipingere per i ricchi. Commissionata da un privato, quest’opera doveva esaltare la qualità delle preghiere del facoltoso cliente, cui non andavano ricordate le umili origini del Cristo. Francesco Datini suggerì agli agenti incaricati di procurare dipinti votivi, di aspettare che gli artisti avessero bisogno di soldi e poi tirare sul prezzo.

Azzuro ultramarino: 2 fiorini circa. Sfondo dorato: 38 fiorini circa. Opera dell’artista: 35 fiorini circa