Bedtimes..

This story was published in the New Yorker

And this one in Vice Magazine

While this little piece was in the New York Review Daily

Le Calme retrouvé

The Burner Burned

«O Signore io… io voglio solamente la tua croce: fammi perseguitare, io ti domando questa grazia che tu non mi lasci morire in sul letto, ma che io ti renda il sangue mio, come tu hai fatto per me». Savonarola aveva sempre agognato la morte. In una società di ambiguità e compromessi invocava chiarezza e confronto. In una città che produceva beni di lusso predicava le virtù della povertà. Non poteva durare. Scomunicato, negò la

legittimità del papa. I bambini presero a sassate i corpi in fiamme.

“Oh Lord… all I want is your cross: let me be persecuted, I beg you this grace, that I not die in my bed, but shed my blood for you, as you did for me.” Savonarola had always sought and foreseen his death. In a society full of ambiguity and compromise, he insisted on clarity and confrontation. In a town that made its living

producing luxury goods, he demanded the virtues of poverty. It couldn’t last. Excommunicated, he denied the Pope’s legitimacy. Children threw stones as the bodies burned.

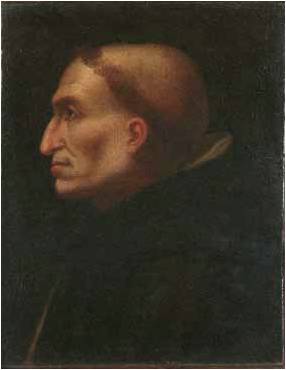

The Face of Fundamentalism – Savonarola

Finalmente un uomo immune a ogni tentazione. Nel 1490, colpito dall’intensità delle prediche di Savonarola, l’umanista e mistico Pico della Mirandola esortò il Magnifico a portare il frate a Firenze, neanche fosse un oggetto, di quelli che i banchieri e gli umanisti amavano collezionare. «Il vero predicatore» rispose Savonarola «non sa blandire i principi, ma piuttosto mordere

Finalmente un uomo immune a ogni tentazione. Nel 1490, colpito dall’intensità delle prediche di Savonarola, l’umanista e mistico Pico della Mirandola esortò il Magnifico a portare il frate a Firenze, neanche fosse un oggetto, di quelli che i banchieri e gli umanisti amavano collezionare. «Il vero predicatore» rispose Savonarola «non sa blandire i principi, ma piuttosto mordere

i vizi loro». Il netto contrasto tra luce e ombra, la testa rasata e lo sguardo intenso esprimono a meraviglia la psicologia del fondamentalista.

At last a man who did no deals, who had no use for the art of exchange. In 1490, impressed by the intensity of Savonarola’s preaching, humanist and mystic Pico della Mirandola encouraged Il Magnifico to bring the friar to Florence. They tried to collect him, as bankers and humanists had collected so much. “The real preacher,” Savonarola responded, “cannot flatter a prince, only attack his vices.” The sharp contrast between light and dark, the shaven head and the intense gaze, wonderfully capture the psychology of the fundamentalist.

Bonfire of the Vanities

Nessun compromesso. Finora l’élite fiorentina e i capi della Chiesa avevano sempre trovato un accordo. Ma Savonarola era inflessibile. «O voi che avete le case vostre piene di vanità e di figure e cose disoneste e libri scellerati» predicava. Mandò i bambini suoi seguaci per la città a raccogliere le opere immorali e i beni di lusso

accumulati dai ricchi. Era tempo di farne un falò. Un secolo di scambio creativo tra opulenza e devozione, tra soldi e metafisica, di colpo s’interruppe.

No compromise. Hitherto Florentine elite and church leaders had always reached some accommodation. Savonarola was inflexible. “Oh ye who have your homes full of vanities, dishonest images and wicked books,” he preached. He sent his child disciples around the town to gather all the sinful artworks and luxury goods the

rich had been accumulating. It was time for a bonfire. A century’s creative exchange between wealth and piety, metaphysics and money was brutally interrupted.

Luxury Gothic

Gotico di lusso. Si sa che nella bottega di Botticelli si discutevano le idee di Savonarola sull’arte. Il frate aveva dichiarato buoni e santi i pittori antichi. Botticelli riprende gli stili del ’300 caricandoli di pathos e presagi. Se la svolta fosse sintomo di una crisi religiosa o solo la ricerca di una possibile nuova moda in linea con i tempi, non ci è dato sapere. Il dipinto è per un cliente privato e, malgrado l’austerità, i colori intensi e le splendide linee evocano una religiosità sontuosa.

Luxury gothic. We know Savonarola’s thoughts on art were discussed in Botticelli’s workshop. The friar had said the old painters were good and holy. Botticelli gestures back to trecento styles, intensifying pathos and foreboding. Whether the change indicates a religious conversion or just an exploration of a possible new fashion to suit the penitential times, we cannot know. The artist is painting for a wealthy client and for all its sombreness, the rich colour and wonderful lines make this a decidedly sumptuous piety.

Lorenzo

«Nelle cose veneree maravigliosamente involto» secondo Machiavelli, il Magnifico condivideva con poeti e donnaioli l’ossessione del controllo. Teneva «la città tanto interamente a

«Nelle cose veneree maravigliosamente involto» secondo Machiavelli, il Magnifico condivideva con poeti e donnaioli l’ossessione del controllo. Teneva «la città tanto interamente a

arbitrio suo» osserva Guicciardini «quanto se ne fussi stato signore a bacchetta». Pagò artisti per promuovere la propria immagine, estetizzando la politica. Questo busto di Torrigiano è forse ispirato a tre statue di cera di Verrocchio e Orsino Benintendi che Lorenzo aveva posto in chiesa per ricordare al popolo il suo carisma.

“Marvellously involved in the things of Venus,” as Machiavelli said of him, Il Magnifico had the poet’s and womanizers’ obsession with control. He “held the city completely in his will”, Guicciardini observes “as if he were a prince waving a baton”. His money paid artists to promote his image, aestheticizing politics. This bust

by Torrigiano may draw inspiration from three wax life-size statues by Verrocchio and Orsino Benintendi that Lorenzo had placed in churches to remind people of his charisma.

Consuming the Madonna

Possibile che siano stati proprio i dipinti votivi il primo genere di consumo sostenuto dalla moda? Se i banchieri avevano invaso la chiesa con le lussuose cappelle private, ora la Chiesa invadeva sempre più la sfera domestica. Gli amici, vedendo un’opera come questa in casa tua, capivano che eri devoto, ricco, e di buongusto. Per un pittore emergente, dare una veste nuova a un vecchio tema – mostrando una Madonna in sfarzosi abiti contemporanei, ad esempio – era un modo per trovare clienti e stimolare la domanda.

Possibile che siano stati proprio i dipinti votivi il primo genere di consumo sostenuto dalla moda? Se i banchieri avevano invaso la chiesa con le lussuose cappelle private, ora la Chiesa invadeva sempre più la sfera domestica. Gli amici, vedendo un’opera come questa in casa tua, capivano che eri devoto, ricco, e di buongusto. Per un pittore emergente, dare una veste nuova a un vecchio tema – mostrando una Madonna in sfarzosi abiti contemporanei, ad esempio – era un modo per trovare clienti e stimolare la domanda.

Were devotional paintings the first fashion-driven consumer product? If the bankers had invaded the church with their lavish private chapels, now the Church increasingly invaded the home. Friends seeing this on your wall knew you were pious, wealthy and had taste. For a new painter on the block, finding a fresh look for an old theme—dressing the Madonna in lush contemporary clothes, for example—was a way of attracting clients and creating demand.

Plato and the Nudes

Platone e i nudi. Patrocinato dai Medici, Marsilio Ficino tradusse e commentò Platone: tutta la bellezza portava a un più alto livello dell’essere e della conoscenza. Allora non serviva più un tema cristiano per rendere “buoni” una poesia o un dipinto; la bella Venere non era solo una donna avvenente ma un’idea, un ideale. E come dice Vasari, Botticelli dipinse per molte famiglie «femmine ignude assai».

Plato and the nudes. Sponsored by the Medici, Marsilio Ficino translated and commented Plato: all beauty was a gateway to a higher level of knowledge and being. So a poem or painting need no longer have a Christian theme to be essentially good; the beautiful Venus was not just a pretty woman, but an idea, an ideal. And as Vasari tells us, Botticelli worked for many families painting “very nude women.”